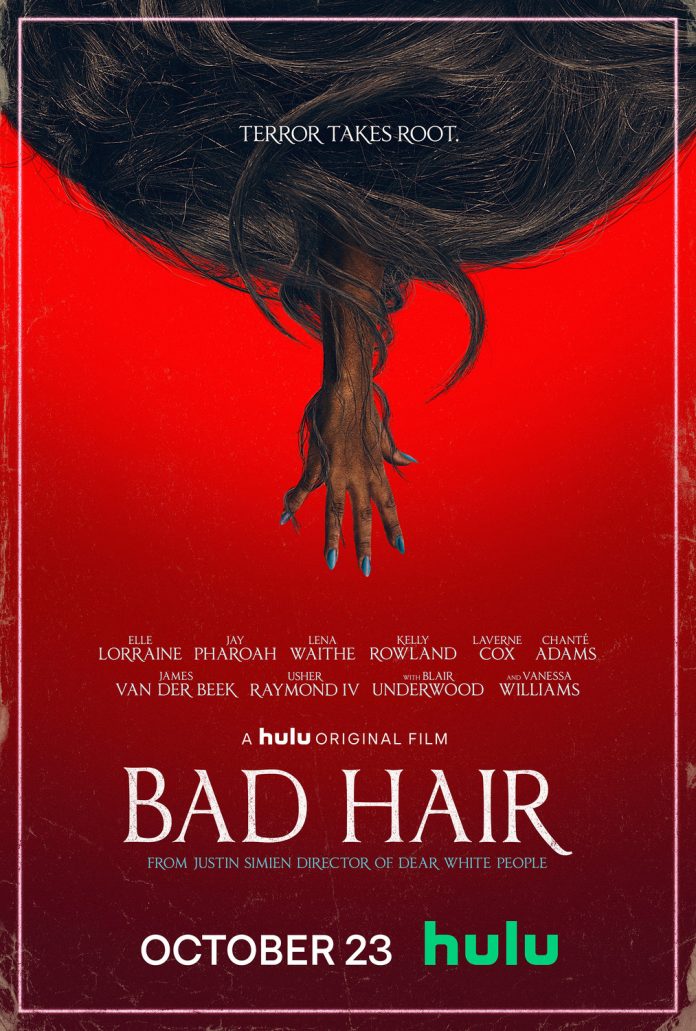

Dear White People’s Justin Simien lends his satirical eye to horror in Bad Hair, a blend of social commentary and pop culture nostalgia wrapped in a supernatural curse film disguised as a workplace dramedy. The end product lacks some of the racial nuances and character complexities of Dear White People, and the script tries too hard in some areas but not hard enough in others, but on the whole, it’s a refreshing genre take on intraracial politics — like School Daze meets The Exorcist.

Set in 1989 in Los Angeles, Bad Hair stars Elle Lorraine as Anna, a wannabe VJ who works behind the scenes at black music channel BET — er, “Culture” — but has been told in no uncertain terms she doesn’t have the right look for an on-camera gig. When former supermodel Zora Choice (Vanessa L. Williams) replaces Anna’s boss as EVP of Programming, she tells her that in order to be one of her trusted “girls,” she needs to ditch her natural hair style in favor of one that “flows freely.”

Eager to advance her career, Anna gets a weave from renowned hairdresser Virgie (Laverne Cox), but as she rises in prominence at Culture — now known as “Cult” — her hair starts to take on a mind of its own. It seems to crave blood and takes over her body in order to feed its thirst by any means necessary. And even worse: others in the company have taken her lead, investing in “good hair” turned bad.

Believe it or not, but Bad Hair isn’t the first horror movie about killer hair extensions — nor even the second. There have been a couple of such films from Japan, most notably quirky auteur Sion Sono’s 2007 feature Exte (the second being a cheap 2014 knockoff called Hair Extension). Unlike the Japanese efforts, which used extensions merely as a conduit for the sort of Grudge-y revenge ghost story we’ve come to expect from J-horror, Bad Hair delves deeper into the social significance of hair extensions — particularly within the black community.

In Bad Hair, the extensions represent the lure of repressing one’s blackness in order to succeed in a world dominated by standards of whiteness — a pressure that, when it comes to beauty in particular, has historically fallen hardest on black women. As Zora tells Anna when she insists on her change of hairstyle: “Sistas get fired for less than that every day.”

From childhood, Anna has been conditioned to believe that straight, long, flowing hair is the ideal — fueled by the insecurity of living with her accomplished uncle and his “good haired” family — leading to a mishap that literally scars her for life. Having previously fallen in with the “natural hair crew” at work, she ends up compromising not only her physical identity but also her professional and moral standards, advocating for Zora’s plan for making Cult more palatable (read: whiter) to mainstream audiences. The underlying message isn’t subtle nor all that novel, but in these genre trappings, it stands out as a morbidly ridiculous precautionary fable.

For all the seriousness of the socially conscious subject matter, the fact that this is the story of murderous, sentient hair ensures that it maintains a campy appeal throughout. Still, its strangely straightforward storytelling fails to buy into its own inherent comedic potential. Aside from Lena Waithe’s role as one of Anna’s coworkers — and the designated comic relief — Simien’s script is surprisingly sober and restrained, only scratching at the surface of its potential for absurdity during the climactic moments.

Simien seems to suffer from “Get Out Syndrome,” wherein he feels the need, as a black genre director, to get “deep” and deliver a mike-dropping hot take on racism, so he ties in a connection to slave narratives and a vague, confusing semi-explanation of the source of the cursed hair that does more damage to the narrative than if it were just left a mystery.

Its shortcomings aside — including some shockingly cheesy CGI effects — as a lifelong black horror fan, I still grin at the fact that a movie about a black woman fighting against possession by hair extensions even EXISTS. Over the decades, I’ve suffered through the genre’s dubious efforts at black representation, from extended periods of invisibility to extended periods of banality. Bad Hair is set in 1989, a year when supporting roles in movies like Death Spa and Headhunter were black horror HIGHLIGHTS, so images like the ones in Bad Hair are a welcome sight — not only because they’re almost entirely focused on black characters, but also because they’re strikingly unique within the black horror aesthetic.

And from a historical perspective, it highlights a couple of components of the late ‘80s cultural zeitgeist that kids today may take for granted: namely, the extent to which music was racially segregated (Hip-hop on pop radio? Not likely.) and the fact that non-straightened, natural hair (aside from braids) was definitely NOT en vogue — as, appropriately enough, the group En Vogue showcased when it was formed in…yup, 1989.