No, Bones and All isn’t a sequel to Bones in which Snoop Dogg teams with laundry detergent to “clean up” the streets© (all rights reserved), nor is it some sort of intricate, erection-centric orgy positioning. Rather, Bones and All is a romance about…cannibals. That’s right; those sexy vampires have hogged the romantic spotlight long enough. It’s time to shine for others who share their thirst for blood but who have no supernatural abilities or any discernible fashion sense.

The cannibal lifestyle portrayed in the movie actually ends up looking like what life might be like for “real” vampires—that is, without the undead, superhuman stuff in the equation. (Hint: it’s a lot less sexy and more depressing.) When adding teen romance into the mix, the result is a bit like Twilight meets Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Or is it Near Dark meets Natural Born Killers? Anyway, there are certainly familiar elements, but they’re handled with poetic aplomb by director Luca Guadagnino (Suspiria, Call Me By Your Name), who takes a measured approach to the content, punctuating it with splashes of jarring violence that provide an undercurrent of menace, spicing up an otherwise bland love story in need of seasoning. (WARNING: MORE EATING PUNS IMMINENT.)

I haven’t read the 2015 novel upon which Bones and All is based, but I’d venture to guess that the lead protagonist, Maren, isn’t black like she is in the film. Played by Taylor Russell (from the much fluffier Escape Room franchise), the cinematic Maren is an 18-year-old who wakes up one morning to find that her non-cannibal father (André Holland) has had his fill of covering up her murders, which began when she took a bite out of a babysitter at age 3. Her desire for human flesh is compulsive and, as it turns out, hereditary, as her dad explains in a “Dear Maren” message he records for her on a cassette tape. Did I mention that the story is set in the 1980s? (1988, to be exact, based on a Ronald Reagan speech heard playing on a radio) His recording serves as a de facto narrator, explaining that her estranged mother was also a cannibal who abandoned the family years earlier, but using her own birth certificate as a clue, Maren sets off across the country to find the mother she never knew.

Along the way, she meets another fine young cannibal, Lee (Timothée Chalamet), and the two kindred spirits grow close over shared experiences with broken homes and a shared love for raw, still squirming food, along with wardrobes seemingly culled from thrift store dumpsters. They “Bonnie and Clyde” their way across the country, leaving a trail of bodies in their wake, with Lee showing Maren the ropes of the nomadic cannibal lifestyle. However, she begins to worry that she’s a monster—a theory bolstered by her encounter with an obsessed “eater” named Sully (Mark Rylance) who begins stalking her. Ultimately, the couple has to face their existential fears and figure out their place in this dog-eat-dog world.

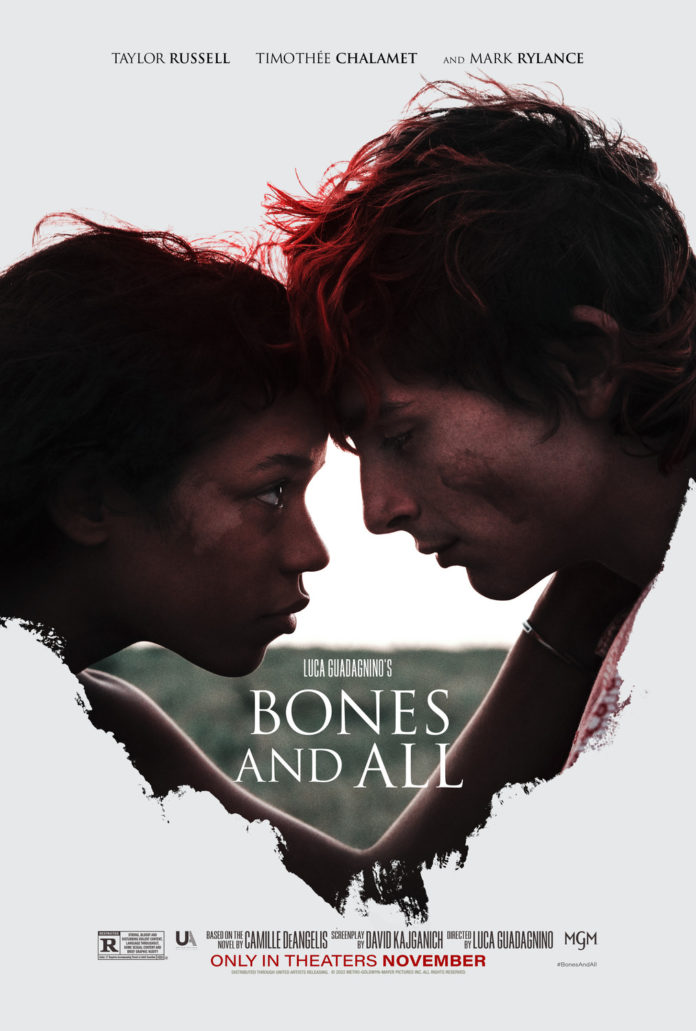

Bones and All presents a fascinating “what-if” scenario that gets bogged down by a love story that feels mundane by comparison. There’s plenty of intrigue in the thread of Maren managing her cannibal lifestyle while navigating through the eater underworld, figuring out who she can trust and simultaneously trying to uncover her mother’s secrets. The Maren-Lee romance is at best the fourth most interesting storyline, but as you can tell by the poster, it’s what takes center stage.

Russell and Chalamet are fine in their roles, but their characters’ mumbly, mopey interactions hardly feel like a cinematic romance for the ages, and for some reason, there seems to be a concerted (and unsuccessful) effort to “ugly” them up with facial disfigurements, weed wacker haircuts and oversized clothing—to the point where their appearance actually becomes distracting, as if their appearance IS their characters because the characters themselves have such little personality. One wonders if any appeal we find in the couple is due to their chemistry or perhaps just due to memories of our own youthful yearnings—romantic fantasies of broken, attractive young people saving each other and traveling aimlessly without any responsibilities or agendas, living in the big-sky wilderness and taking each day as it comes. I’m too old for this shit.

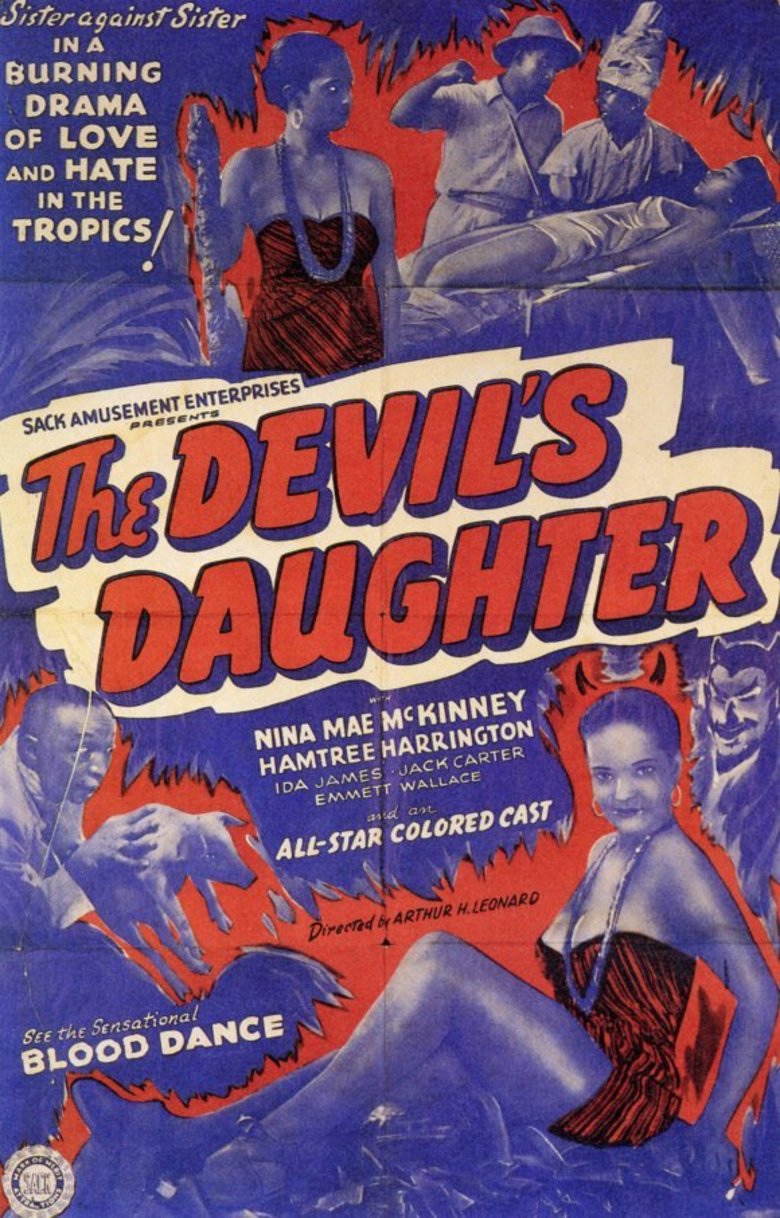

Luckily for horror fans, there’s enough bite in Bones and All to offset its treacly YA inclinations. As you’d expect from a cannibal film, there’s a notable amount of gore, but the film doesn’t wallow in it. A lot is implied; as it turns out, the SOUND of someone eating another human is actually as unnerving as the visual. In between the adolescent yearning, Guadagnino manages to inject a sense of danger that comes with the lonesome life of a Cannibal American, in which you deal with the constant fear of either what you’ll do to someone or what they’ll do to you. Sully (and another pair that Maren and Lee encounter) embodies this threat, Rylance chewing the scenery with his unnerving presence: a creaky, folksy, Pepperidge Farm voice, reservation chic feathered-cap ensemble and the demeanor of a grandparent who secretly keeps child skeletons in his crawlspace. His style and vampiric obsession with the black female protagonist conjures memories of Rebecca Ferguson’s wonderful turn as Rose the Hat in Doctor Sleep.

With Guadagnino being a gay director who doesn’t shy away from homosexual themes, it wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to read the cannibalism in Bones and All as a metaphor for homosexuality. You can imagine a parent talking to their gay child with some of the same phrasing that Maren’s dad uses in his tape: “I don’t know what’s going to happen to you or what should happen to you. I wake up nights sick to death wondering and hoping, hoping that whatever troubles you is over and that if there is a God in Heaven, that you’re just a regular girl with regular problems and regular pain and that you stop wanting things you shouldn’t want, Maren, and that your heart has a chance.” The connection becomes more cemented when Lee goes “above and beyond” with one male victim, seducing him and gifting him “la petite mort” before his actual mort. Of course, the gay metaphor can only go so far before becoming troublesome, given the whole “cannibals needing to murder people in order to survive” thing.

If both leads had been black, Bones and All could perhaps have been interpreted as a statement about the treatment of poor, minority urban populations during the Reagan years, a rough time for both black and gay folk. As it turns out, though, the original novel is actually not that deep and is about veganism (with author Camille DeAngelis stating explicitly that “the point of the book is that flesh is not food”), which is the most straightforward and boring explanation possible.

While Bones and All’s genre-defying nature is an acquired taste, it creates a fascinating universe buoyed by top-tier direction and cast. The ending feels a bit forced and is emblematic of the film’s pathological need to force feed the audience the romance as the main course when the surrounding storyline appetizers are sufficiently filling. </EATING PUNS>