Today, the status of African Americans in horror films is tied intrinsically to the status of African Americans in cinema as a whole. That is, it has come a long way since the wild-eyed tribesmen of King Kong and has even seen notable advances just within the past decade, but there are still significant strides to be made toward a more equitable share of leading roles and roles that aren’t reliant on outdated racial stereotypes.

Race and Representation

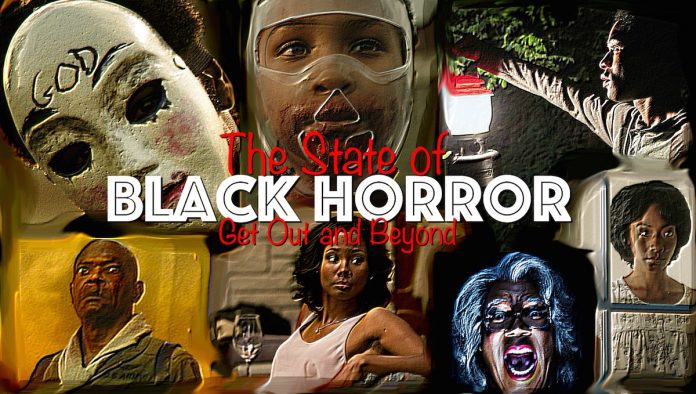

Just as there has been a spike in the prominence of movies featuring black roles in recent years (as evidenced by the fact that the number of black actors and actresses winning Oscars in the four major acting categories thus far in the 21st century has already nearly doubled the number of wins in the entire 20th century), so has there been a spike in the prominence of horror movies featuring black roles. Just within the past year or two, films like Get Out, It Comes At Night, The Purge: Election Year, The Cloverfield Paradox, Kong: Skull Island, The Girl With All the Gifts, Cell, The Invitation, Traffik, The Transfiguration and spoofs Meet the Blacks and the Madea Halloween movies have painted a black face (as it were) on a genre in which African Americans have historically been relegated to fodder for the bloodthirsty villain.

Because of the unprecedented recent level of recognition and critical acclaim for movies with black leads, the state of 2010s cinema has been compared to the Harlem Renaissance, but such unfettered optimism should be tempered by the reality that the annual number of movies produced overall (and horror movies in particular) has exploded over the past two decades, meaning black-featured genre films have benefited from that upward trend. Thanks largely to the increased viability of independent cinema and affordability of filmmaking technology, more than twice the number of movies were released in 2016 (795, per The-Numbers.com) than in 1995 (310). For horror movies, the increase is similar, with the average number of genre films released in theaters annually in 1995-2003 being 13.3 and the average from 2004-2017 topping 27.

That said, while the number of black-featured genre films has increased, and while there are prominent examples that thrive in the limelight, the bulk of American horror (like other genres) remains an overwhelmingly Caucasian affair. Mirroring the underrepresentation that spawned the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag shortly after announcement of the 2015 Oscar nominees, the 2017 Hollywood Diversity Report by UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African-American Studies found that, of the 54 top-earning horror movies from 2011 to 2015, 48 (89%) had casts in which 20% or fewer of the actors and actresses consisted of racial minorities. This came despite the fact that minorities accounted for about 40% of the US population in 2015, and people of color bought 45% of domestic movie tickets that year.

It Follows, for instance, one of the most acclaimed horror movies of 2015, features no major black characters despite taking place in working-class Detroit. Other than half-Iraqi Alia Shawkat (whose ethnicity is never mentioned), the cast of the well-regarded 2016 survival thriller Green Room is devoid of minorities even though the antagonists are neo-Nazi gang members. Other recent prominent genre films, like the colonial-era The Witch and period pieces like Crimson Peak, the Woman in Black films and the Conjuring movies, based on real-life cases of paranormal investigation, have the convenient excuse of historical accuracy to exclude black characters.

The Conjuring movies are part of the current horror trend of the moment: haunted house fare. Beginning with 2009’s Paranormal Activity, the Saw franchise’s “torture porn” era gave way to more traditional ghostly scares, culminating in a slew of hits, including the Conjuring, Insidious, Sinister and Ouija series, plus one-offs like Mama, Lights Out, Oculus, the Poltergeist remake, The Haunting in Connecticut and The Possession. One unexpected bit of collateral damage from this new vogue has been the near-complete exclusion of African-American cast members because, as stereotypically “urban” players, they don’t fit into Hollywood’s vision for suburban (read: Caucasian) domestic bliss turning into a nightmare.

Independent films, however, are not as profit-driven and thus not as concerned with the longstanding fear that black-led films have trouble finding audiences internationally (a belief that was at least partially disproven by the Hollywood Diversity Report, which found that, while movie with casts of greater than 50% minorities haven’t performed well overseas, casts with less than 10% minorities have likewise underperformed; the best performers have had 21-50% minority casts), so indies have proven more amenable to larger, more prominent African-American representation. These smaller, non-studio productions tend to feature roles that don’t fit neatly into the stock Hollywood black character types, which, in horror, tend to include disposable characters like criminals, high school jocks, voodoo practitioners, one-dimensional authority figures and sidekicks willing to sacrifice themselves for the hero.

Urban Horror

That said, the typical indie fright flick still falls short of the 40% non-white representation of the US population at large. Movies with black casts that exceed that level tend to fall into the so-called “urban horror” sub-genre. A modern reincarnation of the black-and-white “race films” and later Blaxploitation fare, urban horror is an offshoot of the overall explosion of African-American cinema during the ’90s that spawned from the success of filmmakers like Spike Lee, John Singleton, Robert Townsend, Mario Van Peebles, Julie Dash and Reginald Hudlin, proving the viability of black films to the major Hollywood studios.

Unlike the works of leading black filmmakers, urban horror movies tend to be low-budget, direct-to-video affairs (with exceptions like Tales from the Hood, Bones, Vampire in Brooklyn and genre comedies like A Haunted House and Meet the Blacks). They frequently revel in “hood” stereotypes, sacrificing plot for hip-hop swagger, as evidenced by titles like Zombiez, Vampz, Bloodz vs. Wolvez, Cryptz, Snake Outta Compton, Hood of the Living Dead and Leprechaun in the Hood. Even the higher quality examples have done little more than mimic successful mainstream films (Scream becomes Holla, for instance.).

In recent years, major studios have found that black female-led thrillers — Obsessed, When the Bough Breaks, The Perfect Guy, No Good Deed, Breaking In — have struck a chord with moviegoers, although again, they’ve mined other popular movies (in this case, Fatal Attraction and its ilk) for content, leaving African-American genre fare without a defining voice. That is, until Get Out.

Get Out and Beyond

It’s hard to underestimate the importance of 2017’s Get Out to the state of black horror cinema. The Jordan Peele film overcame the odds to earn more than any film on horror mega-producer Jason Blum’s resume, including the long-running Paranormal Activity, Purge and Insidious franchises. It also set a record for the highest domestic gross ($175.4 million) for an African-American-helmed film of any genre — a title it held for just a few weeks until F. Gary Gray’s The Fate of the Furious kicked off the summer blockbuster season (followed by the inevitable Black Panther explosion the next year). If you don’t count spoofs like the largely integrated Scary Movie, which grossed $157 million in 2000, or suspense thrillers like Obsessed ($68.2 million in 2009), the most a horror movie with a largely black cast had earned at the box office until Get Out was Candyman‘s $25.7 million in 1992 (and even that film centered around a white heroine).

Get Out‘s success — both commercially and critically, as it earned an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and a 99% rating on Rotten Tomatoes — not only legitimizes black horror to studios (whose modest $5 million investment in its budget illustrates how little Hollywood is willing to risk on African-American films in general, but especially in unproven genre fare), but it also legitimizes black horror to audiences whose expectations for this sub-genre were understandably low. Finally, it legitimizes black horror for filmmakers interested in the genre and sets a high bar of excellence, while reawakening the possibilities in the genre for allegory, satire and social commentary.

The story of a black man (Daniel Kaluuya) visiting his white girlfriend’s family, only to find them pathologically obsessed with his race, Get Out tackles racial dynamics head-on, taking Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner to Stepford Wives extremes in order to hit home the prevalence of racial prejudice in all walks of life and in more guises than people would care to admit.

It’s an in-your-face approach that might not have resonated with non-white audiences five years ago, when many people were insulated in a bubble of self-proclaimed post-racialism, but given highly publicized incidents of racially motivated violence, police brutality and the racially charged 2016 Presidential campaign, it found its mark. It remains to be seen whether horror — a genre known for jumping on trends — will see the release of other similarly pointed black films, but just as it took a string of successful black movies to convince studios that there is a market for African-American cinema as a whole (something that seemingly has to be proven every decade or so), it may take similar convincing to build on Get Out‘s success. In fact, we may need to wait and see how Peele’s follow-up, Us, performs in 2019 before Hollywood truly gives into black horror. In terms of proving the box office potential of black films, Jordan Peele might be horror’s Tyler Perry.

The contemporary horror movies that most closely resemble Get Out‘s approach are the Purge films. Like Get Out, they utilize hyperbole based on the reality of social inequality. While the Purge franchise is more focused on economic schisms, such divisions are inextricably tied with race, and as such, each of the movies in the series has featured major black characters struggling to survive against rich, mostly Caucasian elitists who view them as expendable.

Within the context of social movements like the Occupy movement, Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and the Women’s March, these films (each seemingly more politically charged than the one before it) have struck a chord with audiences, propelling the franchise to sustained success through three entries, with a fourth, the prequel The First Purge, due later this year. Notably, it’s the first in the series with mostly black leads and a black director, Gerard McMurray. In terms of determining the commercial viability of black horror in the minds of Hollywood studios, The First Purge is likely the most important film since Get Out.

But flying under the radar are horror movies with less pointed messages about race that are nonetheless just as vital in advancing the black presence in horror. More than ever before, black actors and actresses are being cast in fright film roles that aren’t race-specific. Whereas a few years ago, the entire premise of the thriller Lakeview Terrace revolved around one man’s (Samuel L. Jackson) contempt for a neighbor’s interracial relationship, the 2017 thriller It Comes At Night revolves around an interracial couple, and yet race is never mentioned. The same goes for 2016’s The Invitation. The title character in the 2017 zombie film The Girl with All the Gifts is black, but she could just as well be Caucasian, Asian, Latina or any other race. Same goes for Gugu Mbatha-Raw’s starring role in The Cloverfield Paradox.

Compared to Get Out‘s blunt approach to race, this integration strategy is more subtle, and it appears to be more common in indie films — although 21st-century genre films like 28 Days Later and Alien vs. Predator pulled it off nicely. While it’s perhaps susceptible to falling into the sort of color-blind mentality that fails to account for any level of racial sensitivity, this sort of gradual assimilation can help normalize the presence of black protagonists as merely a reflection of reality — something for which studies like the Hollywood Diversity Report strive.

Regardless of whether a horror movie’s approach to race is direct or subtle, its impact would be limited if the film itself was not good. The power of Get Out is that it not only educates, but it also entertains, and neither aspect would be wholly successful without the other. It’s this level of quality — not just from Get Out, but from a string of horror films in the past year or two featuring prominent black roles — that could make this a watershed period for black horror. Sure, there is still forgettable, low-brow urban horror fare, but it’s increasingly tempered by more original, more thoughtful, more skillfully put together films. While Get Out, It Comes At Night, The Girl with All The Gifts, The Cloverfield Paradox, Traffik and The Invitation get more publicity, recent low-budget works like The Transfiguration, The Alchemist Cookbook, They Remain, Unsullied, Parasites, The Sickle, Initiation and Soft Matter have similarly helped up the ante for black-led horror. And on the horizon are promising films like the satirical Bad Hair from Dear White People creator Justin Simien and Slice, starring Chance the Rapper and Zazie Beetz, from sizzling hot indie studio A24 (Moonlight, The Witch, Hereditary, Lady Bird, Ex Machina, Room, It Comes at Night).

In the ’90s, black cinema — including urban horror, which dwindled by the early 21st century — was wrung dry, stretched thin and then discarded, as if all aspects of black life had been fully explored. It was a post-racial lie that Hollywood told itself, foreshadowing the post-racial label that was to accompany the Obama presidency — a label that Peele set out to repudiate in Get Out. Now, appropriately, Get Out is part of the next great wave of black cinema, helping to define a voice for black horror that can’t be so easily dismissed or extinguished.