In the US, Black domestic servitude still conjures antiquated images of Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen birthin’ babies and whatnot, a concept that is, as they say, gone with the wind. In countries like Brazil and South Africa, however, domestic servitude goes hand in hand with Blackness, an ever-present reminder of a prolonged and deeply entrenched racial hierarchy. Not surprisingly, those two nations have long boasted some of the highest levels of wealth inequality in the world, but while Brazil has made significant strides in improving that gap during the 21st century, South Africa, despite freeing itself from the yoke of Apartheid 30 years ago, continues to see the average White resident earn nearly three times that of the average Black resident. Whites make up only about 10% of the South African population but account for the majority of the richest 5% of the citizenry — and perhaps more tellingly, they make up only 1% of the more than half the population that lives in poverty. It’s little wonder why South Africa has earned the ignominious title of the world’s most unequal country.

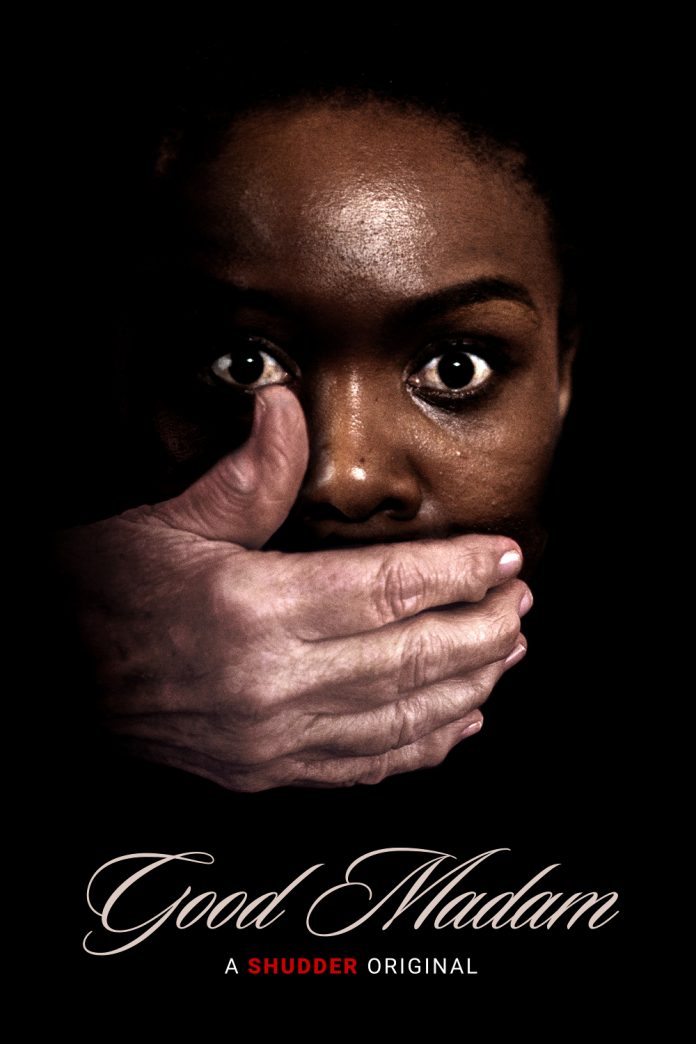

This backdrop provides rich context for the film Good Madam, a searing and thoughtful dive into the country’s legacy of racial and social status and how it continues to haunt South Africans a generation after the end of Apartheid. The story follows Tsidi (Chumisa Cosa), a single mother who, after the death of her grandmother — who raised her like a daughter — is desperate for a place to stay and ends up moving in with her estranged birth mother, Mavis (Nosipho Mtebe). Mavis lives in affluent Cape Town suburb Constantia (about 80% White and 100% judgmental), a world away from Tsidi’s former home in the all-Black urban township Gugulethu. Mavis has for decades been a live-in domestic worker for a wealthy White family, all of whom have moved away except for the bed-ridden matriarch, Diane, AKA “Madam” (Jennifer Boraine).

Tsidi finds Mavis as devoted as ever to Madam, who remains behind closed doors, summoning Mavis periodically with a small, Pavlovian bell. Tsidi spent some time in the house as a child and has always disliked it, at least partly because of an unspoken grudge over it separating her from not only Mavis, but also from Tsidi’s brother Gcinumzi (Sanda Shandu), who lived with Madam throughout his childhood under the anglicized name Stuart. Soon after moving back in, Tsidi finds even more reason for animosity towards the sprawling home: it seems to house a supernatural force targeting her family. With nowhere left to run, she’s forced to face the mystery head-on, uncovering dark secrets that threaten all she holds dear.

Good Madam is a prototypical slow burner that doles out details deliberately and thus requires some patience. We don’t get a grasp of the malevolence until late in the film, and you may even find yourself pausing just to get a grasp of who the characters are (some are referred to with multiple monikers) and what their relationships are to one another. Given a little leeway, though, you’ll be rewarded with a rumination on the saliency of racialized roles in South Africa that is haunting in the sense of both a horror movie (with some chilling imagery, particularly during the climax) and an incisive think piece about the affluent White viewpoint of the Black “help” as property, little more than the tribal statues and carvings that permeate Madam’s abode.

It’s noteworthy that Good Madam comes from female creatives — and wholly appropriate, given that the great majority of domestic workers in South Africa and across the globe are women. White South African Jenna Cato Bass, who co-wrote the wonderful 2018 Kenyan romance Rafiki, serves here as co-writer, director and cinematographer. She makes the most of a limited budget with oodles of atmosphere that hyper-focuses on sights and sounds, closeups and exaggerated ambient noise that bring the house — haunted by the sins of the past — to life. The script was co-written by Black South African Babalwa Baartman (although most of the main cast receive a writing credit, perhaps an indication of some level of improvisation), who helped cast Mtebe, a domestic worker who had never acted previously, as Mavis. Mtebe and Cosa bring naturalness to their roles, whose relationship forms the core of the story — a showcase for Black mothers and daughters being still something of a rarity in horror movies.

You can certainly see how some might want to label Good Madam as a South African Get Out. It touches on similar themes of possessive Whiteness objectifying and commodifying Blackness, but I find it has just as much in common with the 1974 Brazilian film Angel of the Night, which delves into the generational trauma festering, even subconsciously, within Black servants subjugated by their White bosses. At one point in Good Madam, Tsidi tells her daughter, “It’s not that Mama doesn’t like this house, but it seems this house doesn’t like Mama,” which echoes a sentiment from Angel of the Night that the White master’s house isn’t friendly or welcoming and, in fact, can be the source of evil. In Angel, Black night watchman Augusto states at one point, “My boss’s grandfather built the wrong house in the right place.” Indeed, just as the racial wrongs of Brazil’s past cursed the home in Angel of the Night, so did the injustice of the Apartheid era curse the home in Good Madam — along with, it seems, a good portion of South African society.