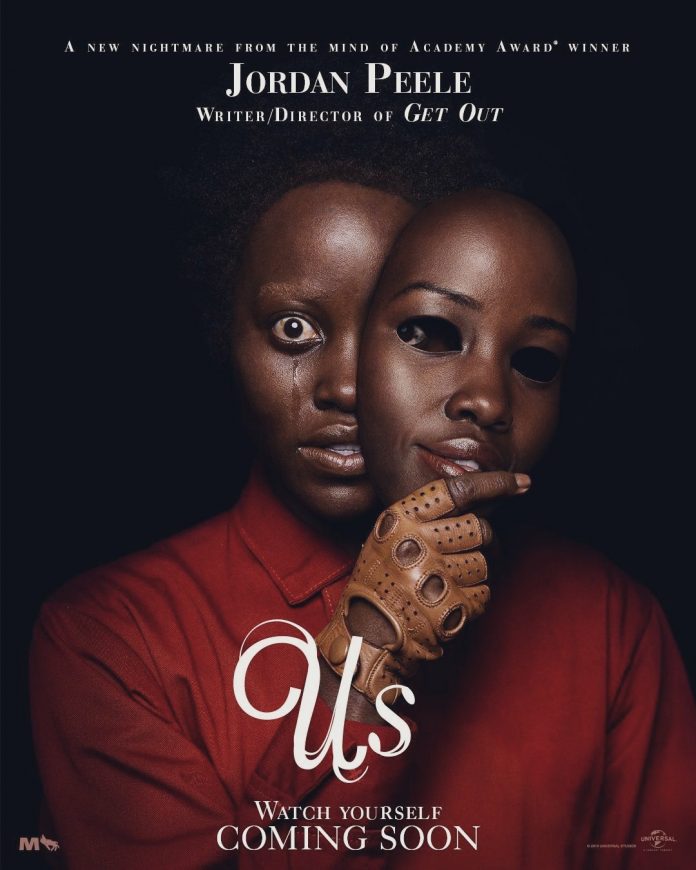

In the days leading up to the release of Us, writer-director Jordan Peele took to Twitter to declare — presumably in response to critics who are all too eager to label his film a “social thriller” or some such nonsense — that it is indeed a horror movie. Unlike Get Out, though, this isn’t a horror movie I would recommend to non-horror fans; it’s more harrowing, violent and nightmare-inducing than Peele’s debut — as my rattled wife, who walked out of the theater and spent 15 minutes of the home invasion sequence listening from the hallway, would attest. As the credits rolled, I expected her to want nothing more than to wipe the memory of Us from her mind, but a funny thing happened on the way to the car: she couldn’t wait to discuss its meaning.

Such is the magic of Us. It’s a horror movie about…us. As such, it’s open to as broad a spectrum of interpretations as there is a broad spectrum of people in the world. Whereas Get Out’s message about race was relatively straightforward, Us is less easily digestible. It’s a democratic movie that means different things to different people, making it as American a cinematic experience as any.

Broader in scope — both physically and thematically — than Get Out, Us is set in and around the coastal town of Santa Cruz, California, the location of a childhood trauma suffered by Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o). Years later, adult Adelaide is vacationing with her husband, Gabe (Winston Duke), and two children, Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex), when her past comes back to haunt her in the form of a group of doppelgangers who look just like the Wilsons — and who seem dead set on killing them and taking their place.

The overriding theme that runs throughout Us, then, is duality. Of course, that’s a vast, ages-old motif that has a myriad of permutations. Is Peele using it to talk about the economic schisms between the haves and the have-nots? Is he referring to the sins of the past haunting those in the present (something particularly relevant in this era of comeuppance for perpetrators of sexual harassment and racial discrimination)? Or, given the central family is black and upper-class, is this an exploration of the balance between success and loss of racial identity — “keeping it real,” as it were? Having taken my share of college English courses, I can tell you that the answer to all of these questions is “Yes”…if you can provide adequate support for your thesis.

*SPOILERS FROM HERE ON*

Above all, though, Peele is delving into the moral dichotomy of humanity as a whole. Adelaide’s evil twin, dubbed Red, refers to herself as a “shadow,” echoing the Jungian psychological term for the unconscious “dark side” of one’s personality. While this is a universal concept, Peele relates it specifically to the United States (Us = U.S.) and the sort of fanaticism (be it hyper-patriotism, racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia or religious intolerance) that is all too willing to demonize the “other.” When Adelaide asks who the invaders are, Red responds, “We’re Americans.” They’re us. We may want to blame them for our troubles, but in truth, they’re no more evil than we are (as the final twist — perhaps predictable but still effective — affirms).

Anyone who’s been on social media can tell you we’re living in an us-versus-them era in which one side is 100% right and the other side is 100% wrong. The lack of civility in social discourse is a collective shadow, and Peele is holding up a mirror, asking us to take a long, hard look at ourselves before we point fingers. In one scene, Jason even recites the old adage that when you point at someone, there are three fingers pointing back at you.

The shadows, or the “Tethered,” aren’t so much evil as they are products of their environment. Us turns out to be a case study for the “nature versus nurture” debate, revealing that the Tethered could easily be conditioned into becoming “normal,” functional members of society — at least, if they start young. Left to their own devices, however, with limited resources and only an implanted drive to mimic those above ground, they became monstrous abominations, a dark reflection of ourselves. When this darkness is ignored (trapped in a physical equivalent of Get Out’s Sunken Place), it’s bound to erupt — in this case, with an orgy of violence culminating in a perversion of one of the last cultural touchstones Adelaide remembers: Hands Across America. The final image of a miles-long, red-clad human chain encapsulates the dark side of American unity, as the Tethered announce their arrival, intent on making America…great again?

Us is much more heady than it appears on its surface and requires some deciphering to truly appreciate. It’s thus not as instantly enjoyable or as crowd-pleasing as Get Out and demands multiple viewings before delivering a verdict. That said, it’s still fun (with more of a sense of humor than you’d expect), wildly imaginative and beautifully shot. Some questions remain — like the nature of Adelaide’s tethering situation after the switch — but these are details you’re willing to overlook when the material is this captivating. Peele has proven himself to be a leading voice in horror, an innovator who’s forcing the mainstream to (reluctantly) admit that the genre isn’t the sewer it has always envisioned — the Tethered of cinema, so to speak.

Peele’s decision to have black protagonists in his films provides an exhilarating boost of racial representation, the sight of a black nuclear family in a horror movie being a rarity, as I’ve pointed out before. In Us, their presence is all the more potent given they’re meant to represent a typical (albeit well-off), all-American family — “all-American” generally coded language for “white.” But despite the color of the cast (who excel in their dual roles, Nyong’o in particular), Us ostensibly doesn’t seem to be about race. Dig a bit deeper, though, and you can see that it’s about race as much as the history of America is about race. It’s about sexism, xenophobia and homophobia in the same way. Because it’s about us.