With his remarkable feature debut His House, British writer-director Remi Weekes achieves what seasoned horror filmmakers struggle to pull off: tackling social issues like immigration, xenophobia, genocide and gender roles, alongside weighty themes like psychological trauma and grief, all while delivering throat-clenching scares. It’s one of the rare movies that can be enjoyed simultaneously by horror fans as a straight-up fright flick and by non-genre fans as a wrenching, timely drama.

His House follows married South Sudanese refugees Bol and Rial Majur (Sope Dirisu and Wunmi Mosaku), who flee the armed conflict of their homeland and end up seeking asylum in England after their boat capsizes, killing many of their fellow escaping countrymen — including their young daughter, Nyagak (Malaika Wakoli-Abigaba). After being held by authorities for several months, the couple is finally allowed their release “on bail,” meaning they’re assigned a home to test their ability to “get along, fit in” — but under a strict set of regulations, including a prohibition against acquiring jobs and having guests.

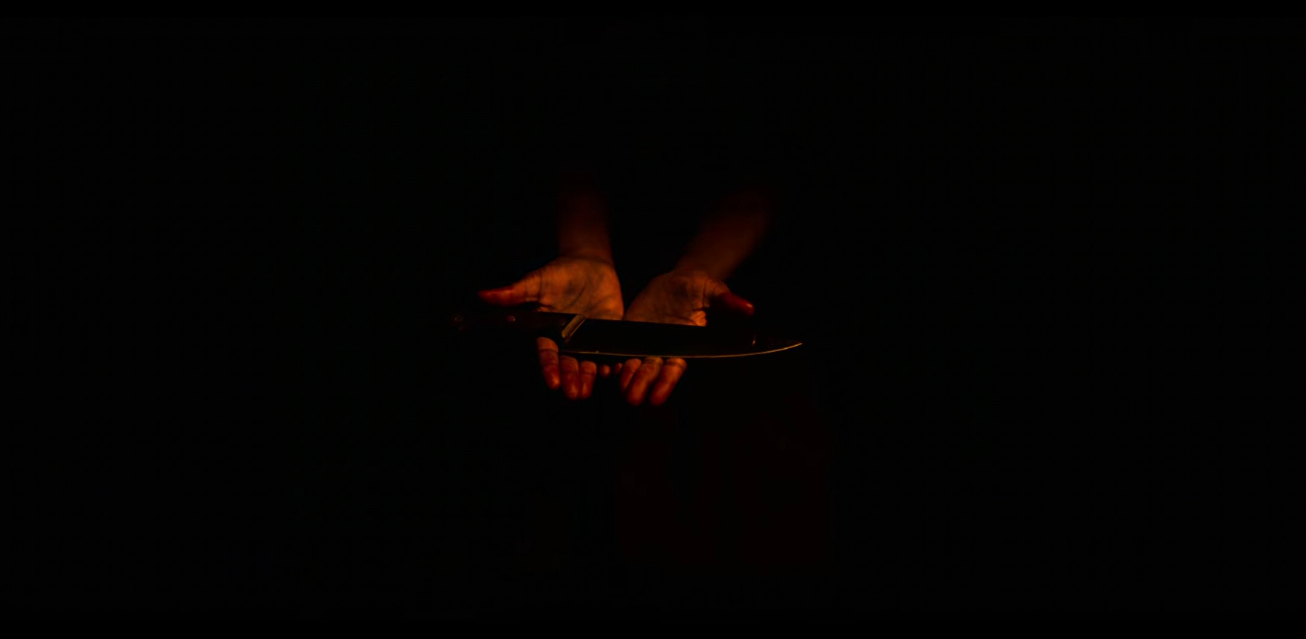

Shortly after moving into their dilapidated house nestled in a seedy urban area, Bol and Rial begin to — in typical haunted house fashion — hear strange noises and see shadowy figures. It quickly becomes evident that there are supernatural entities within their walls, and while the stubborn Bol feels the brunt of their aggression, Rial takes a more pragmatic approach: “After what we have seen, what men can do, you think it is bumps in the night that frighten me? You think I can be afraid of ghosts?” But the malevolent forces have plans for Bol, and the couple must figure out how to release him from their grasp.

I’ve written before about how few black families are featured in haunted house movies, and compared to the minor examples that have popped up here and there (A House Is Not a Home, Dream Home, First Born and Boo, etc. — not counting kids movies like The Haunted Mansion), His House blows them out of the water in terms of both prominence (snagging a Netflix spotlight) and quality. The story is deceptively simple and light on dialogue but carries depth — not only narratively speaking (with a particularly devastating plot twist), but also in its observations on the social and emotional complexities of the refugee experience. Weekes is able to fill in the gaps of dialogue with harrowing scenes of danger faced in both South Sudan (via flashbacks) and their new home, imbuing the imagery with a dreamy visual flair without sacrificing a scare factor that rivals modern haunted house standard-bearers like Paranormal Activity, Insidious and The Conjuring. And Dirisu and Mosaku pull it all together with a mix of the sort of strength and vulnerability that characterizes survivors of trauma.

While His House has a typical (read: white) haunted house movie setup — a grieving couple trying to start anew in a home occupied by a supernatural entity — the fact that the protagonists are foreign refugees living in an urban setting opens the possibility that they, according to the Acceptable Cinematic Racial Roles (ACRR) Handbook, can be black. Interestingly, though, race isn’t explicitly called out in the film as an issue. Granted, Bol and Rial’s blackness sticks out in their mostly white surroundings, but so do their attire and their accents, which help identify them as immigrants. The most direct antagonism they encounter, in fact, is from a group of black Brit boys who tell Rial to “go back to Africa.”

Although race always plays a role in everyday life, this story is more concerned with the immigrant/refugee experience. It shows glimpses of the unimaginable real-world genocidal horrors of their homeland, followed by the indignities of being at the mercy of an asylum system in the UK that seems inherently distrustful of foreigners and more concerned with conformity to ease a presumed burden on citizens. “Make it easy for people,” Bol is told by caseworker Mark (Matt Smith); “Be one of the good ones.” The movie’s title is in part a reference to a dismissive reaction from one of Mark’s co-workers to Bol’s request to change houses: “His house is bigger than MINE.” In other words, be grateful for what you have — a response that’s familiar to minorities everywhere when they complain about discrimination and disparate treatment.

As specific as the circumstances for Sudanese refugees are, there is universality in His House’s core theme of dealing with trauma and grief. Weekes’ insightful script uses the couple to illustrate two different, but equally flawed, approaches to coping: Bol is too focused on moving forward and forgetting the past, while Rial is too focused on the past, unrealistically trying to recapture a lost moment in time. It’s a fascinating dichotomy in which each spouse needs the other to balance their shortcomings, and it ends up an unexpectedly touching testament to the power of marriage.

An immediately essential viewing experience that ranges from poignant to petrifying, His House is the latest in a series of modern horror movies — including Get Out, The Witch, The Babadook, Hereditary, It Follows, Relic, etc. — that has moved the needle in terms of how the genre is perceived critically. The days of dismissing all horror as cheesy “slashers” are gone, and the genre is consistently delivering films every year of such high artistic merit that they can no longer be swept under the rug when awards season comes. Get Out managed to score a Best Original Screenplay Oscar in 2018, and His House has the heft — from a social, emotional and creative perspective — to aim at least as high. Given the quality of the story, performances and direction, it would be hard to justify overlooking His House when the Oscars roll around.