*SPOILER ALERT* In order to fully discuss this movie, I’ll need to reveal its major plot points. Sorry.

Also: *IGNORANCE OF BRAZILIAN CINEMA ALERT* Sorry again.

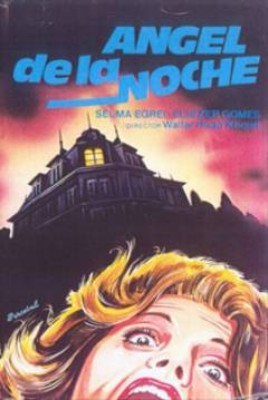

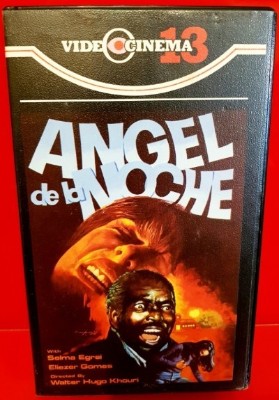

Although the late Walter Hugo Khouri was a highly acclaimed and accomplished Brazilian director, his movies are ponderously difficult to find; at last check, only one of his 25 feature films is available on Amazon.com — and it’s a used VHS copy. Even on the Brazilian Amazon site, there are only two of his DVDs for sale. This means that in order to see O Anjo da Noite (The Angel of the Night), one of his two forays into horror — along with 1978’s As Filhas do Fogo (The Daughters of Fire) — you most likely will have to watch a painfully grainy, low-quality version uploaded to YouTube in black and white even though the movie itself was shot in color. (A restored version played in Brazil in 2012 but for some reason doesn’t appear to have led to a DVD or Blu-ray release, although based on the images below, there apparently were some ’80s-era VHS releases under the Spanish title Angel de la Noche.)

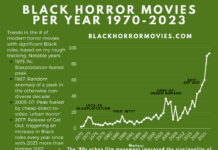

That’s a shame because even through the scratchy, bunny-ears quality, you can tell that O Anjo da Noite is an atmospheric modern Gothic film that should be more widely recognized by horror fans around the globe. A shadowy slow-burner full of dread and creepy ambient sounds — crickets chirping, grandfather clocks ticking — it’s a fascinating slice of cinematic history from a country whose horror output is little known in the United States outside of José Mojica Marins’ Coffin Joe movies, and, as it turns out, it’s a film that can be appreciated not just as an old dark house flick, but also as a somber commentary on social ills.

On its surface, the plot is a simple retelling of the urban legend about the babysitter and the anonymous crank caller. In this instance, it’s a 23-year-old psychology student named Ana (Selma Egrei) who travels from Rio to the mountain town of Petrópolis for a weekend babysitting gig at a secluded mansion. The wealthy couple that lives there, doctor Rodrigo (Fernando Amaral) and his socialite wife Raquel (Lilian Lemmertz), has two young children: Carolina (Rejane Saliamis), who sleeps through most of the film, and Marcelo (Pedro Coelho), who in that era might be deemed “precocious” but in truth is a spoiled and potentially sociopathic little shit.

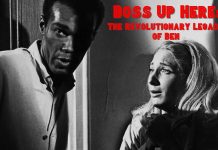

The only other person on the property is Augusto (Eliezer Gomes), the black, middle-aged night watchman who patrols outside throughout the night. You’d think that sense of security would put Ana at ease, but not when she begins receiving phone calls from someone threatening to kill her. Eventually, as the ordeal goes well into the early morning hours, it’s revealed **SPOILER ALERT** that little shit Marcelo is behind the calls. BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE: when Ana receives one more ominous call after Marcelo is scolded and put to bed, she finds Augusto on the other end of the line. With a wild look in his eyes, he proceeds to shoot her AND the kids dead. It’s When a Stranger Calls…And Then Another Stranger Calls And Straight-Up Murders Everyone.

So, what gives? Is Augusto a crude stereotype of black criminality? You might initially think so, but upon closer viewing, it’s evident that he’s taken over by some sort of supernatural impulse that drives him to kill. For most of the film, he’s an amiable, gentle soul, explaining to Ana that he prefers to work outdoors because the house isn’t “friendly.” The implication is that there’s something inherently wicked about the building. “My boss’s grandfather built the wrong house in the right place,” he tells her. Augusto is forced to venture inside, however, when the calls begin, and as a result, something possesses him, propelling him into a murderous rampage. Only when he finds himself back outside at the end of the film does he regain his senses and realize what he’s done — and he screams in terror.

There’s no clear explanation of what the mysterious force is that pushes Augusto over the edge, but there’s compelling evidence that it’s a reflection of the deep-seeded social — specifically, racial and economic — schisms that have long plagued Brazil. Its economic inequality makes the US look downright socialist in comparison (Case in point: the six richest men in Brazil have the same wealth as the poorest 50% OF THE POPULATION.), and Afro-Brazilians disproportionately fall into the lower wealth brackets, with a poverty rate twice that of white Brazilians and with even college-educated blacks earning between 40% to 70% of white counterparts.

The schism is evident early in O Anjo da Noite when the family’s black driver picks Ana up and brings her to the house. There, we see that all of the other servants are also black except for the governess, Beatriz (Isabel Montes), who clearly holds rank over the “help.” The fact that Ana is white is no coincidence; we see her reading a letter that Rodrigo sent her babysitting agency requesting that the nanny have “good looks,” which, as Brazilian film scholar Laura Loguerchio Canepa points out, is a euphemism for whiteness. (It could certainly be a double entendre; Rodrigo wants her to be white AND hot, because, frankly, he seems like a letch.)

In addition to the people inside the house, the building itself is a testament to the legacy of racial exploitation and violence born of slavery and colonization. Its sprawling opulence far exceeds the needs of a family of four, spurring Augusto to comment that, although he also has a wife and kids, he prefers his small, modest home. Despite its size and ornate decorations, the mansion is cold and foreboding, decorated with violent imagery like statues of sword-wielding angels and antique firearms. In one powerful scene, as the force begins to overtake Augusto, we see him facing a wall of guns, all pointing towards him in a menacing and symbolic fashion:

Even the setting of Petrópolis is itself noteworthy in that it’s renowned as a wealthy tourist destination. Nicknamed “The Imperial City,” it served as the summer home for the Brazilian monarchy and aristocracy during the 19th century; significantly, in the story, Raquel mentions that she and Rodrigo are leaving town to attend social functions related to the queen’s visit.

I won’t pretend to be an expert on Khouri’s films, but from what I can gather, they tend to portray, as scholar Daniel Serravalle de Sá puts it, “the malaise of the Brazilian bourgeoisie,” and true to that theme, Raquel and Rodrigo come off as blasé and snooty, their hands-off approach to child rearing leading to kids who are, according to Beatriz, “fragile.” Given their secluded, idyllic world, Augusto’s rampage is all the more shocking — not only within the realm of the film, but also for those watching it. As de Sá comments, “Khouri’s film shows awareness of the possibilities that would strike fear in a bourgeois audience in relation to their domestic workers…The night guard develops a gradual but unconscious perception of the mediocrity that he is doomed to watch and live. The indifference of the Brazilian bourgeoisie to the angst of those living on the margins of society erupts in this conclusion as a horrifying and threatening Gothic manifestation.”

Certainly, a wild-eyed black man menacing a white woman can be a troubling image from a racial representation perspective, Augusto’s hypnotized, lumbering gait as he approaches Ana resembling Darby Jones in I Walked with a Zombie. Check out this creepiness:

But with a sociopolitical reading of the film, you can see how this portrayal serves a purpose. He’s possessed not by a traditional demon, but by a demon of society’s making. The house is haunted not by a ghost, but by sins passed from one generation to the next. It’s cursed not by the traditional trope of a murdered innocent, but by murdered innocence, hope decimated by systemic racism, inequality and deprivation of human rights.