*OBLIGATORY SPOILER WARNING*

With the release of Jordan Peele’s eagerly anticipated third film, Nope, it’s fair to say that his filmmaking style has been established. A Peelian movie is horror-skewed genre fare that seeks to entertain but also convey underlying social commentary — directly or indirectly racial in nature and often related to the fateful hubris of man taking on forces beyond his reach — while peppered with symbolism and pop culture Easter eggs that spawn water cooler conversations, BuzzFeed lists and more online theories than a Q prophecy.

Like Peele’s scripts for Get Out and Us, Nope prominently features a biblical quote (Get Out’s quote from Romans 12:1-2 was in the script but omitted from the film), opening with the text from Nahum 3:6: “I will cast abominable filth upon you, make you vile, and make you a spectacle.” The operative word here is “spectacle,” a recurring theme throughout this horror-sci-fi hybrid that takes aim at society’s fascination with that which is larger than life (“how we observe spectacle and our addiction to it”): the unreal reality of reality TV, the sponsored clout-chasing of social media, the sensationalism of tabloids and clickbait articles, the alarmism of news reports, even the calculated blockbuster Hollywood productions that try to one-up one another but end up sterilizing their content by trying to appeal to everyone all at once. They’re all competing for our increasingly short attention spans, and Nope, boasting a effects-heavy budget ($68 million) nearly triple that of Peele’s previous two efforts combined, knowingly places itself in the middle of that dogpile; it’s a spectacle movie about spectacle.

Nope plays like a love letter to the king of Hollywood spectacle: Steven Spielberg. It’s clearly inspired by Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Jaws, the latter of which ushered in the era of the summer blockbuster. In this sense, Peele isn’t averse to the power of spectacle, but having come through the Trump presidency and the COVID pandemic and still living in the era of TMZ and millennial social media influencers, he knows that sensationalism is a double-edged sword.

In the film, an alien invader (a “sky Jaws,” as it were) terrorizes a dusty, isolated California community, and Peele portrays the perils of trying to harness such a wild creature, physically or metaphorically (via photos or video). The pursuit of spectacle when driven by a “quest for attention” can be disastrous, as several characters discover — most notably Ricky “Jupe” Park (Steven Yuen), a former child star who operates a tourist trap theme park based (loosely, for copyright reasons) on his decades-old supporting role in the movie Kid Sheriff. Having lost his shot at stardom after a tragic chimp attack on his follow-up sitcom Gordy’s Home caused the show to be shut down, he is seeking to re-establish a following — literally chasing “Viewers,” his term for the aliens he’s secretly been luring to the area. By living in the past under his fake cowboy persona and telling war stories of the chimp incident with a morbid fascination, Jupe succumbs to his performative self, not realizing that in showbiz, the viewers ultimately consume you. Ironically, though, in the end, his sense of spectacle — a giant balloon in his image — ultimately is the weapon that takes down the rampaging extraterrestrial.

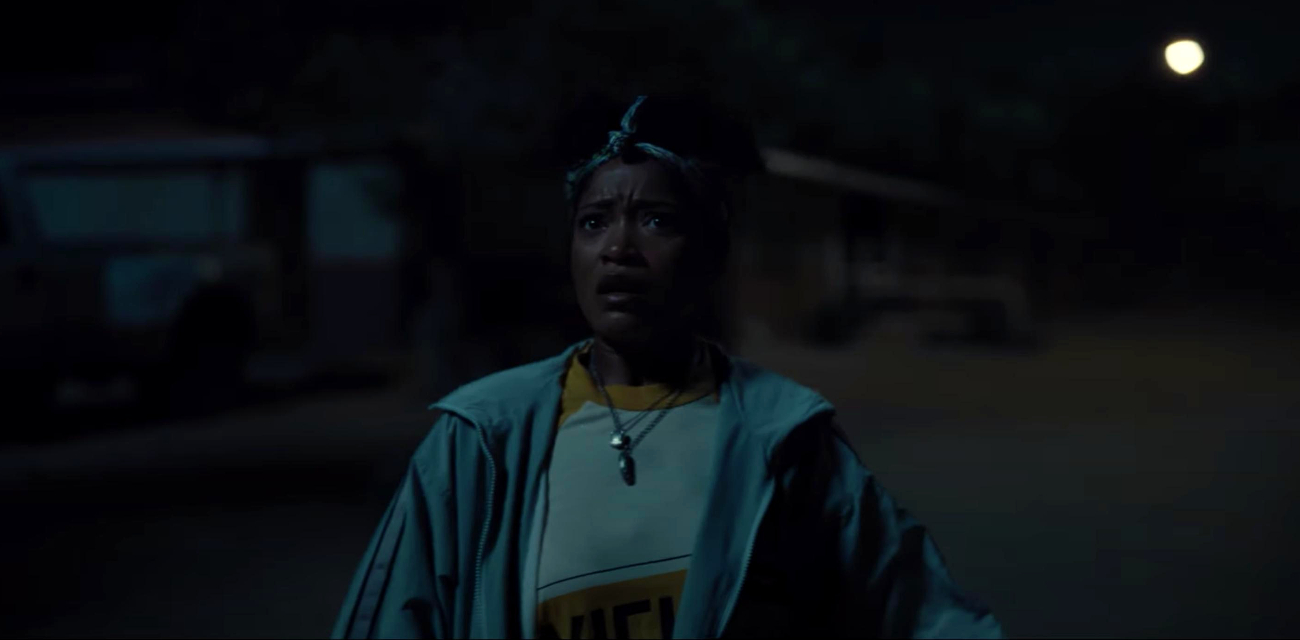

The balloon highlights the positive side of spectacle, as do the main protagonists in the story: siblings O.J. (Daniel Kaluuya), responsible but aloof, and Emerald (Keke Palmer), charming but flighty. Following the death of their father (Keith David) from a seemingly freak accident, they find themselves struggling to keep his horse wrangling business — which specializes in training horses for movies and TV — afloat. When they observe the alien in the clouds above their home, they hatch a plan to capture it on video, convinced that that will earn them enough money to save the business.

O.J. and Emerald’s ambition differs from Jupe’s, however, in a couple of crucial ways. First, their experience with animals makes them more prepared; it helps them decipher the alien’s tendencies and shapes their strategy for dealing with it. Second, their motivation is not simply a “quest for attention” for attention’s sake. They have a sense of purpose that traces not only to their father, but all the way back to their great-great-great grandfather, the jockey portrayed in Eadweard Muybridge’s groundbreaking 19th century proto-motion picture chronophotographic experiments. The jockey is a figure whose name has been lost to history, but Peele reimagines him as an ancestor of this Black horse wrangling family business. To the public at large, he is nameless and forgotten, perhaps the very first victim of the spectacle of movies. His fate was a forerunner of that of other Blacks and POCs that showbiz would chew up and spit out over the coming decades (like Jupe and another child actor in Kid Sheriff, who are remembered as “the Asian one” and “the Black one”). Instead of being used and discarded like their great3 grandfather, O.J. and Emerald want to be creators of the footage this time around and profit from it. They want to be the pioneers, the ones who are remembered in history books. They have the legacy of their family at stake, as well as a sense of righteous vengeance, as it turns out their father was inadvertently killed by the alien. All of this validates their quest as moral and just; they are cloud chasers, not clout chasers.

Nope is the sort of tea-stirrer we’ve come to expect from Jordan Peele. By design, it’s bigger, brighter and tonally more fun than Get Out and Us, even if the film itself is the least of the three. Of course, that’s less of a slight against Nope than it is high praise for Peele’s first two efforts. Nope is still highly entertaining — harrowing, with some dazzling visuals, enough twists and mysteries to keep you on your toes and a rousing climax. The weakest parts are the sluggish pacing early on and the seeming under-utilization of Oscar winner Kaluuya, whose character operates in a glum stupor throughout — although he’s offset by Palmer’s vivacious, scene-stealing performance. Like all of Peele’s movies, you feel like you need to go back and rewatch it to catch everything and formulate your theories, a fun exercise that rekindles our joy for cinema — the positive side of Hollywood spectacle.